Abduction: Mozart’s opera was made for ‘superhuman’ voices

Victorian Opera’s Abduction will premiere in August at the Palais Theatre. In this article, Conductor Chad Kelly delves into the music’s complexity and “vocal fireworks” that were tailor-made for only the most talented singers.

Let me now turn to Belmonte’s aria […] Would you like to know how I have expressed it – and even indicated his throbbing heart? By the two violins playing in octaves. This is the favourite aria of all who have heard it, and it is mine also.

I wrote it expressly to suit Adamberger’s voice. You see the trembling, the faltering, you see how his throbbing breast begins to swell; this I have expressed by a crescendo. You hear the whispering and the sighing – which I have indicated by the first violins with mutes and a flute playing in unison.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart penned these words to his father, revealing careful details in composing his dark comedy, The Abduction from the Seraglio. The opera premiered in the summer of 1782 in Vienna’s Burgtheater, captivating an audience of powdered-wig aristocracy with its nimble score.

As this fragment of Mozart’s letter lays out, he composed the music with specific singers in mind. And he certainly gave them a challenge: for example, a character must plunge to one of the lowest notes written in opera, others rise rapidly to soaring high notes, and all must articulate an early form of patter (rapidly sung script).

Chad Kelly is the Conductor for Victorian Opera’s take on the opera, Abduction. He says Mozart packed his arias with “vocal fireworks” to platform the mind-blowing extremes of the singers’ agility.

“Who was Mozart writing for and who was he collaborating with? In the case of Entführung [Abduction], we know there was a stellar cast of people Mozart knew, including his friends. And he wrote this music bespoke for these characters in his life,” Chad says.

One particularly difficult role to cast is Osmin, the henchman of Pasha Selim, Chad explains. Mozart wrote this role specifically for a renowned German singer, Ludwig Fischer.

“Ludwig Fischer reportedly had this ridiculous, almost superhuman range, almost like he has three voices in one. We’re blessed to have Luke Stoker, an Australian singer who’s returned from working in Germany, to sing this role.”

So how might audiences react to such complex music? Chad says that unlike Idomeneo – Mozart’s cerebral, high-brow opera written a year earlier – The Abduction from the Seraglio is immediately engaging and, like fireworks, a pleasure to behold.

“Even though Entführung is very difficult to sing, it’s not actually complex in the way Idomeneo is. It’s quite direct and accessible, and in a weird way it’s quite simple,” Chad says.

“You can have simple music with extreme virtuosity.”

Our version of Abduction has taken creative liberties with the original libretto (script) and structure.

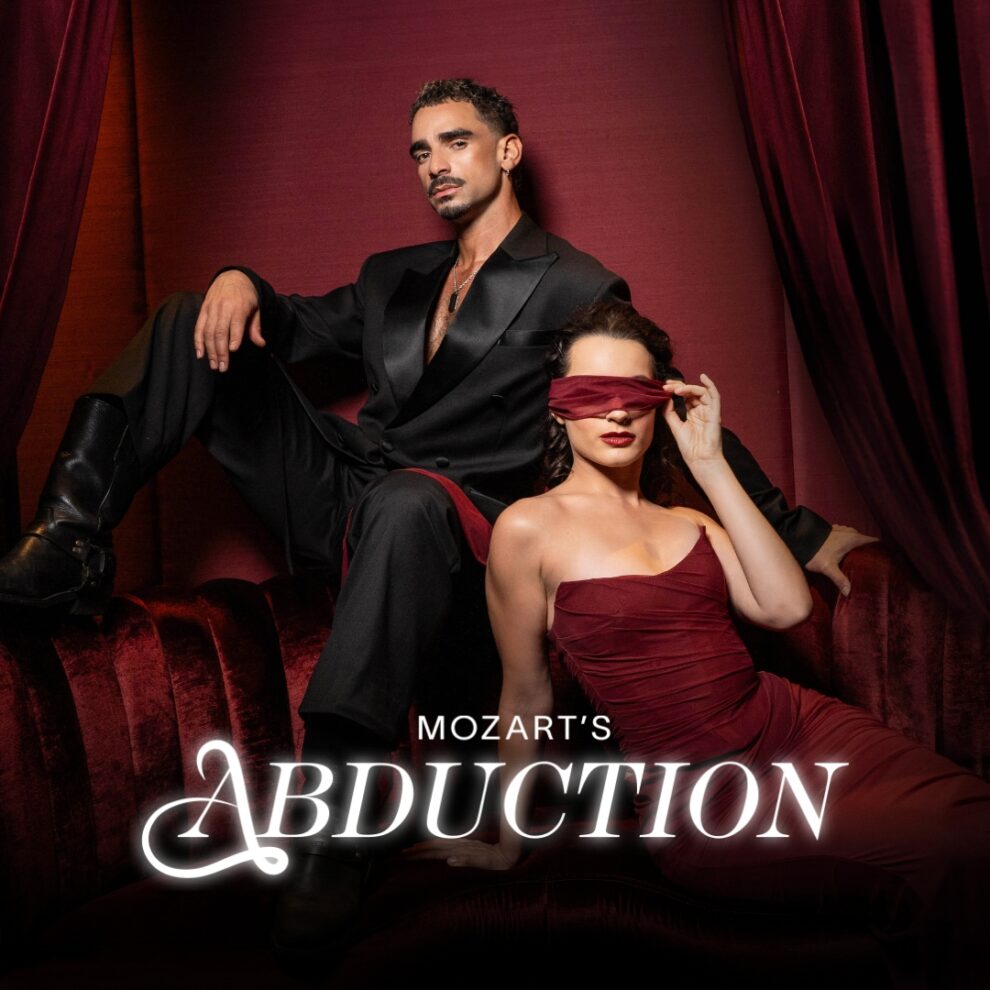

Under the leadership of Director Constantine Costi, we’ve swapped a Seraglio for a lavish, velvet-draped club – think The Great Gatsby meets Rocky Horror. Throw in thigh-high boots and sexually frustrated heroes, and our Abduction is a boldly unique staging for a 21st century audience.

“The story we’re telling is very much the one we want to tell, rather than us trying to transport a story from 200 years ago to today’s audience,” he says.

Yet, Chad’s approach to Mozart’s music is steadfastly true to its history. He contemplates every note, beat and bar, every shape of musical phrase, to ensure it’s as close to an 18th century performance as possible.

Read more: Constantine Costi on how Mozart’s pioneering sex comedy made opera history

“Whenever you’re performing music of the 18th century, I believe it’s imperative to engage with the way people would have played back then. It’s a style of playing which is different to the way most orchestra’s play Mozart. It sounds different, it feels different to what you hear today.”

In the past 250 years, the way we interpret orchestral scores has changed. For example, when an 18th century musician would read a slur (notes played without breaks) on a musical score, it usually implied a diminuendo (softening of sound). A 21st century musician reading the same music today might well do the opposite, Chad says.

“If you play on the page, it’s not enough, you have to play with all the awareness of back then. There’s a lot that’s implied and not written.

“My mission will be to bring that out.”

Anthea Batsakis, Content Editor