The intensity and unrequited love affair of composer Leoš Janáček

Ahead of our performances of Katya Kabanova, writer Ben Minarelli spoke to conductor and Janáček specialist Alexander Briger about the enduring legacy of the composer, and the difficulties in bringing Katya to the Australian stage.

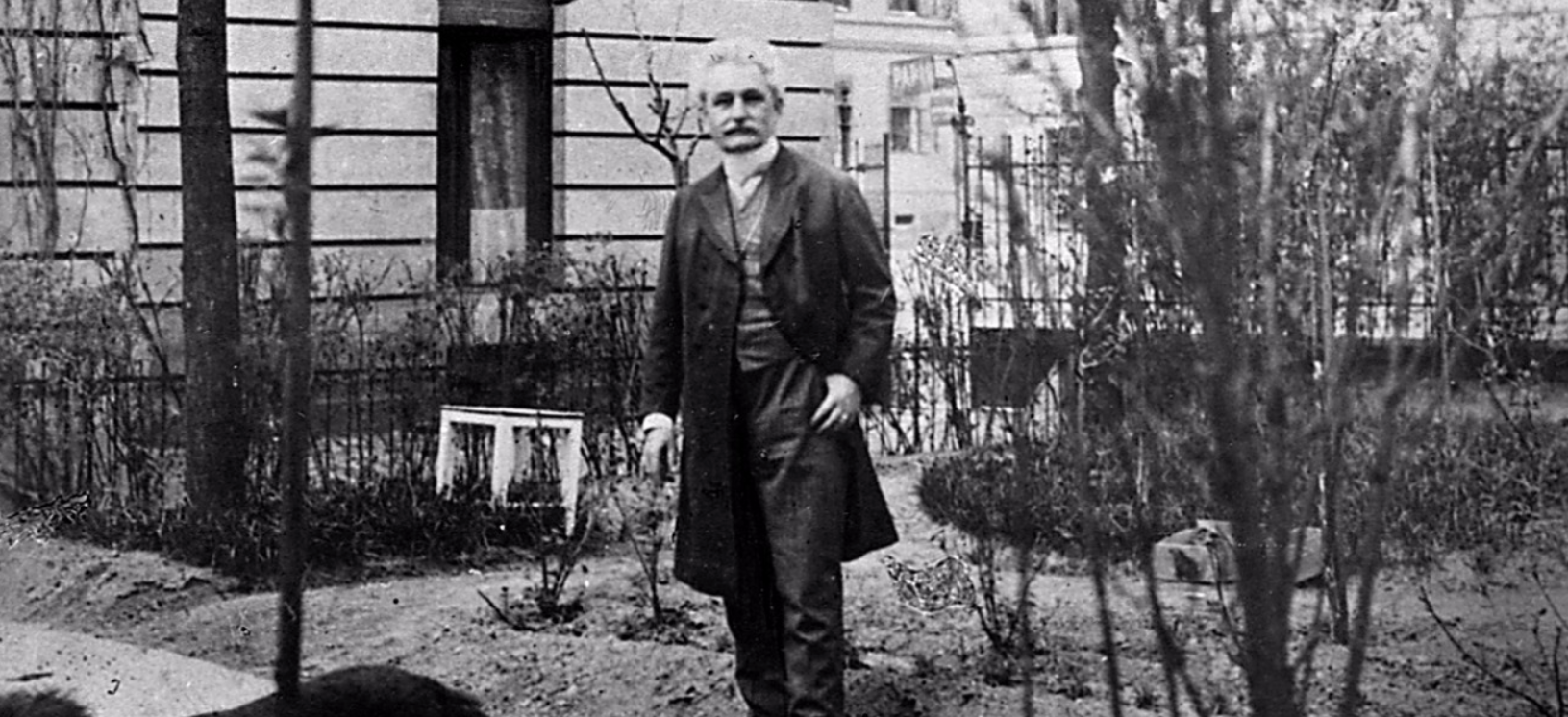

At the turn of the 20th century, amid the political turmoil and hard-fought revolution that would one day lead to the formation of Czechoslovakia, a Czech composer was carving astonishing new depths in opera: Leoš Janáček.

His first opera Jenůfa had a patchy journey to success. Written and performed in the early 1900s in Brno, Janáček’s home and a city outside Prague, Jenůfa featured dark themes of betrayal and infanticide. Janáček dedicated the opera to the memory and suffering of his own daughter Olga who died a year earlier.

With unconventional melodies and strong folk music influences, Jenůfa initially struggled to appeal to audiences. This problem was compounded by Janáček’s personal rivalries and professional criticism of contemporaries – an unwise move against the very people who could boost the profile of his work.

It took over a decade for a revised version of Jenůfa to be staged in Prague’s National Theatre and, at last, Janáček received critical acclaim, just shy of his 62nd birthday.

Alexander Briger, Conductor and Janáček specialist, says Jenůfa is a harbinger of the distinctive style his operas would go on to possess: unvarnished realism, drawn from love, loss and desire in his own life.

“For me, Janáček is one of the top three opera composers to have ever lived,” Alexander says. “I think his works are what opera should be. Relatable, and accessible to audiences.”

Janáček’s muse and music

It was around this time – when Janáček was thrown into national acclaim after 1916 – that the composer became infatuated with a much younger, married woman named Kamila Stösslovà.

Despite the 38-year age gap and being already married, he dedicated much of the rest of his life to this emotional affair, dedicating many of his works to her and writing her hundreds of love letters.

“All his operas are about her, in a way,” Alexander says. “And she couldn’t have cared less about classical music. She didn’t care about him at all! He was this old man who was obsessed with her, a woman who has no interest in him and his great passion.”

Katya Kabanova was one such Kamila-inspired piece, and is considered one of Janáček’s best works. Based on The Storm, a play by Alexander Ostrovsky, Katya is a tragic fable of love and longing set in a rural Russian town.

Janáček dedicated Katya Kabanova to Kamila Stösslovà and filled the opera with the same passion that tortured Janáček himself. This spills into the love duet between the heroine Katya and her lover, Boris.

The score is a perfect example of the distinctive, punchy style his operas are famous for. This style incorporates “speech melodies”, based on inflections of Czech speech over somewhat sparser orchestrations than many of his contemporaries.

This clipped manner of speech allegedly imitates how Janáček himself would speak with former students.

Desiree Frahn is the soprano taking on the titular role of Victorian Opera’s production of Katya Kabanova. She says Janáček writes music “that flows like natural speech”.

“There are no set arias or repeated choruses, no backtracking. The story moves forward with the music, and the score adds emotional depth and nuance to the text that wouldn’t be possible on its own,” she says.

“It feels like heightened dialogue, shaped by the characters’ inner lives.”

Scribbled notes, impossible keys

Janáček was a difficult man in life, and this difficulty carried over into his composing style. Alexander Briger says the original manuscripts are “like Beethoven’s, with scribbles everywhere, all over the place”.

“You can’t tell if it’s a double sharp, or one sharp, there are impossible keys and tempo changes,” he says.

Janáček wrote extensively on musical principles of his own design, many of which informed his less conventional methods of composing. Alexander likens understanding the music Janáček wrote as an act of interpretation.

“You’ve got to sit down and work it out. He’s constantly changing meter, almost like he just forgot what he was doing the night before, then came back in the morning to start again, doing something completely different,” he says.

“You have to work out how this tempo relates. And it does! But it’s not intuitive.”

Performing Janáček to modern audiences has become possible due to the hard work of Australian Conductor Sir Charles Mackerras. Noting that many of the published versions of Janáček’s operas in circulation were revisions or adaptations by other composers, Sir Charles spent much of his life piecing together the original manuscripts.

Alexander Briger is Sir Charles Mackerras’ nephew. He says Sir Charles republished many restored parts and adapted them into more modern notation methods. These now form the basis for any modern performances of Janáček’s work.

Alexander expresses his uncle’s significant legwork. He says: “if you don’t have [Charles’] parts, when you get to that first rehearsal, you won’t even get to conduct! All you’ll be doing is explaining Janáček’s notes and it becomes a nightmare.”

Relatable, beautiful, moving

Part of the enduring legacy of Janáček as a composer is the relatability of his works. Dealing with grounded, tragic events and focusing on people with relatively low social status gives his work an approachability that many, more fanciful operas of the previous centuries were unable to tap into.

His operas were also quite well paced – often around 90 minutes long. With real, stark, human stories at the fore, it’s no wonder these works have managed to capture hearts around the globe.

“The stories are incredibly intense, really involved, and they also relate to us as human beings. You can actually imagine these stories happening,” Alexander says.

With such universal themes, rich music, and weighty inspirations, Janáček’s work is an important part of opera’s cultural history that will continue to grace stages the world over.

Victorian Opera’s production of Katya Kabanova is one more note in this symphonic legacy.

Ben Minarelli